Former Ichnoplanet students Martín Farina, Verónica Krapovickas and co-authors have published a study on mammalian trackways from the Neogene Vinchina (Middle to Late Miocene) and Toro Negro (Late Miocene to Early Pleistocene) formations, in the La Rioja Province Vinchina Basin, Argentina!

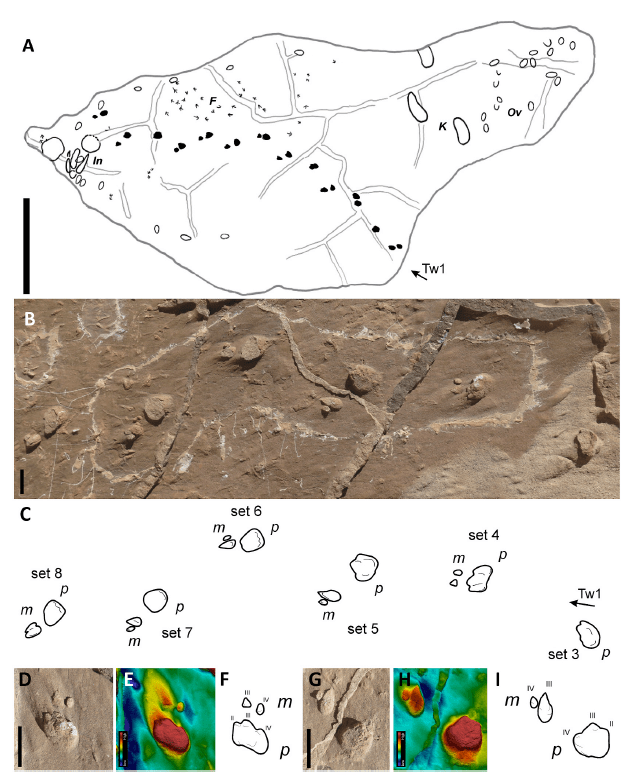

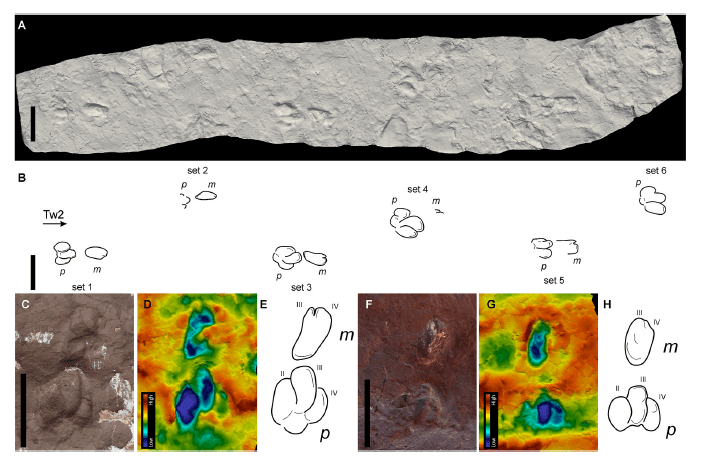

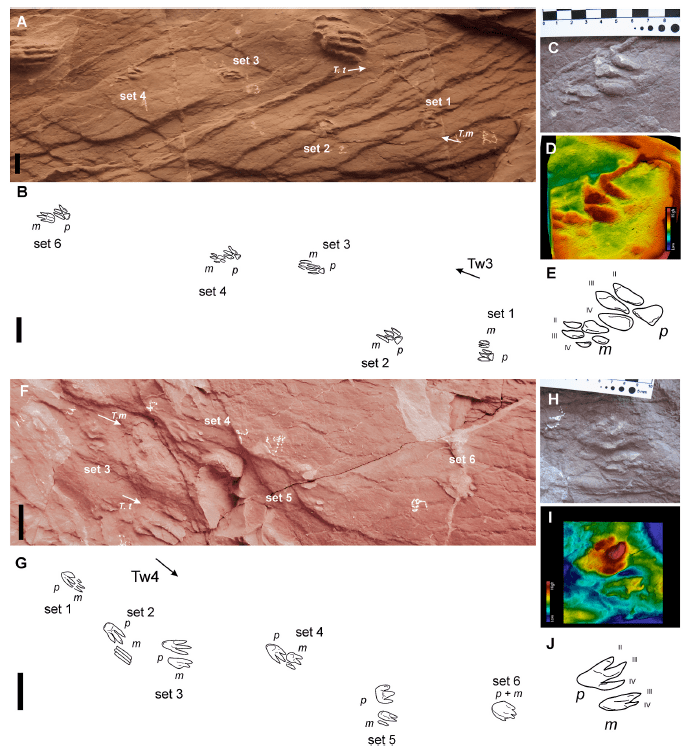

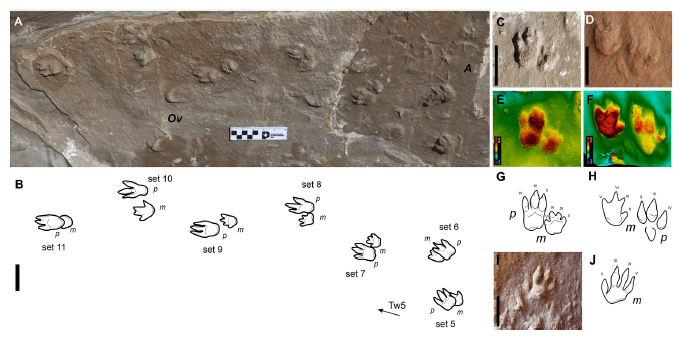

Northwestern Argentina has an outstanding ichnological record of the Cenozoic vertebrate faunas. This study reports five mammalian trackways and the diversity of the trackmakers responsible. Of the four ichnospecies identified, three are new. The trackways come from deposits interpreted as floodplains of both meandering and anastomosed fluvial systems.

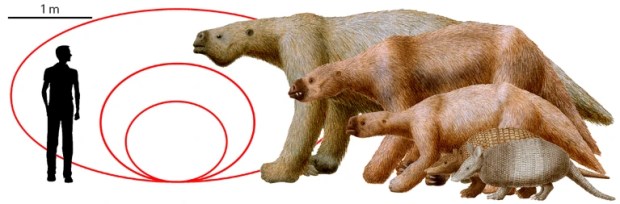

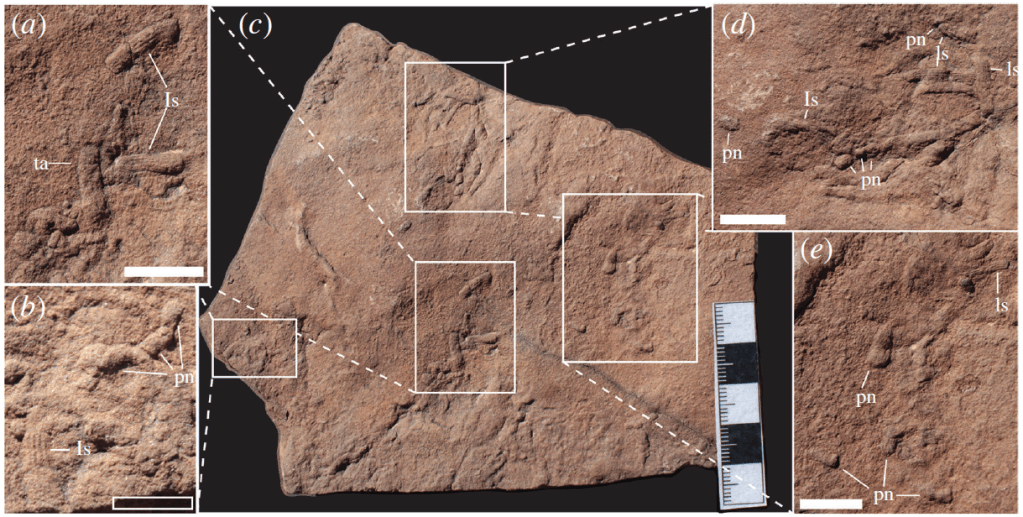

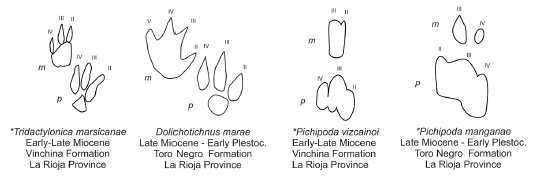

Pichipoda is a novel ichnogenus that has a didactyl to monodactyl manus and tridactyl mesaxonic pes impressions with robust digits with blunt tips. Two ichnospecies are assigned to Pichipoda, including P. manganae and P. vizcainoi. P. manganae (P. manganaei) is the largest ichnospecies of Pichipoda and has a didactyl manus, and the manus of P. vizcainoi shows an almost monodactyl morphology. Tridactylonicha marsicanae is another novel ichnogenera and ichnospecies, described by a tridactyl to didactyl paraxonic manus and tridactyl mesaxonic pes impression with long, slender, and pointed tips of the toe impressions. Dolichotichnus marae has tetradactyl paraxonic manus and tridactyl mesaxonic pes impressions.

P. manganae and P. vizcainoi are interpreted as being produced by armadillos, with P. vizcainoi being attributed most likely to tolypeutines. Before this study, ichnofossils attributable to fossil armadillos were unknown, meaning this is the beginning of our understanding of the trace fossil record of this group and can help us to ask further paleobiological questions. T. marsicanae is interpreted as being produced by hegetotheriids, a family belonging to the extinct group of South American ungulates, the Notoungulata. D. marae is most likely produced by dolichotines, a group of caviid rodents.

Astute readers will notice the etymology of P. manganae honours our very own Dr. Gabriela Mángano, which we here at Ichnoplanet firmly endorse. The contributions Dr. Mángano has made to ichnology are unmatched, and it is fitting that these newly described trace fossils act as a reflection and reminder of her great career.

Congratulations to the authors, including Martin and Verónica, on this amazing study. We know the continued research into the small mammal trackways of Cenozoic Argentina is filling in an important gap in our understanding of vertebrate faunas within South America, and we await what new discoveries have to say.

Read the paper in the Journal of South American Earth Sciences here.

Written by Jack Milligan