Dr. Romain Gougeon, Dr. Gabriela Mángano, Dr. Luis Buatois, Dr. Guy Narbonne, Dr. Brittany Laing, and Dr. Maximiliano Paz have just published their research on bioturbation at the onset of the Cambrian Explosion within the monograph series Fossils and Strata. This is the culmination of 4 field seasons that took place from 2016 to 2021 at the Cambrian-type section in Newfoundland. The monograph consists of a comprehensive ichnotaxonomic review that is essential to understanding the Cambrian explosion from a trace-fossil perspective.

Romain Gougeon and colleagues conducting fieldwork in Newfoundland, Canada. See Fossils and Strata for open access monograph.

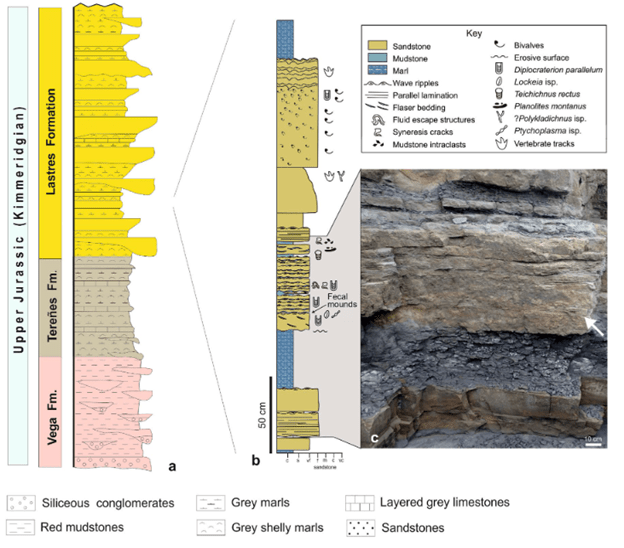

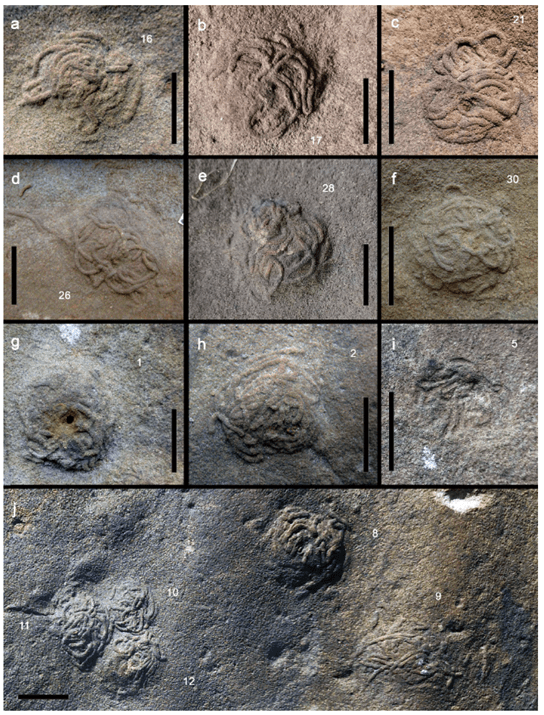

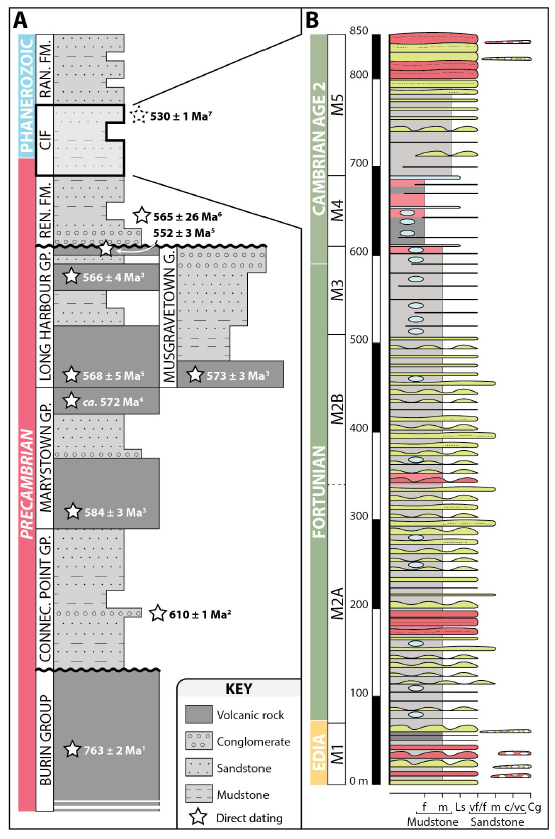

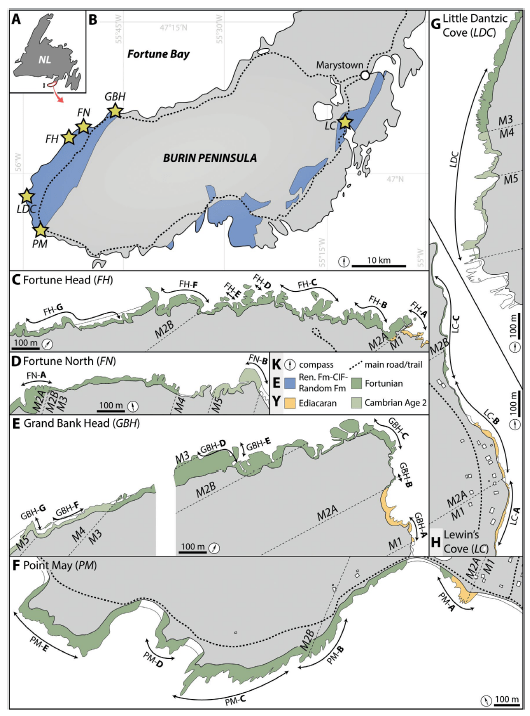

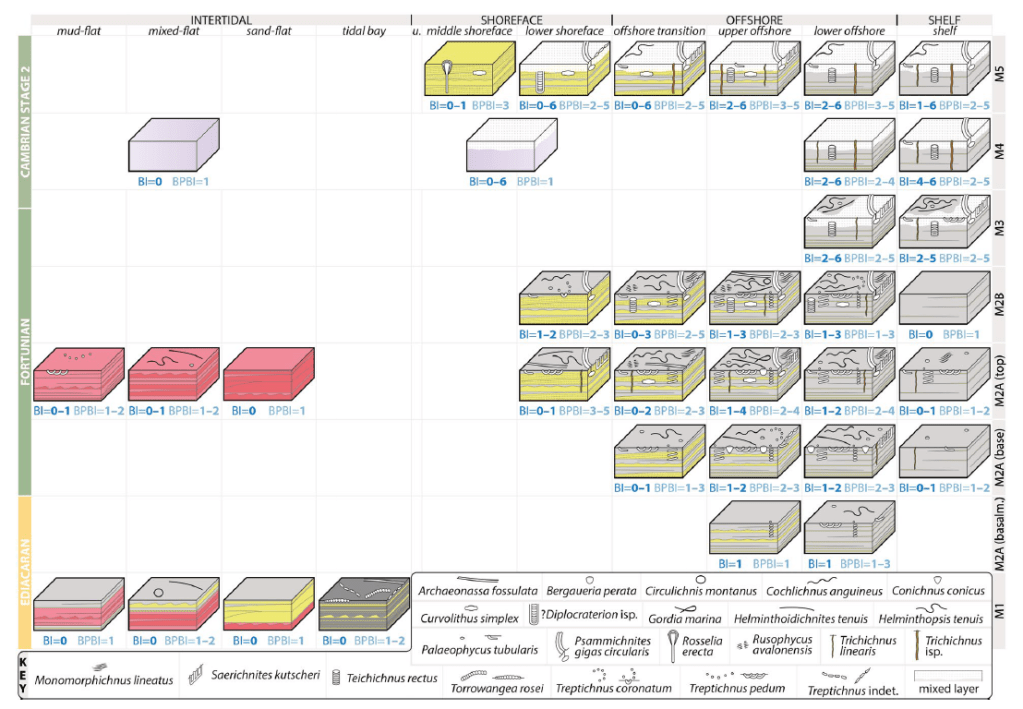

The Chapel Island Formation is a 1000+ m-thick, mainly siliciclastic succession that is well-exposed in coastal cliffs of Burin Peninsula, southeastern Newfoundland, eastern Canada. This unit contains an outstanding record of the transition from the Ediacaran (635–538 Ma) to the Cambrian (538–487 Ma). Fossils from the Chapel Island Formation include an incredible diversity of trace fossils, with some intervals rich in small shelly fossils. The monograph integrates sedimentologic and ichnologic information for the whole formation, reinforces the status of the current Cambrian Global Stratotype Section and Point for the Cambrian System, and advocates for the need for more comprehensive and multi-disciplinary approaches and studies to fully decipher the scale, tempo, and loci of the early evolution of animal life on Earth.

Congratulations to Romain and the team on this incredible achievement! You can check out Romans’ ResearchGate profile here, where you can read other studies he’s authored on the Chapel Island Formation throughout the years. These include the origin of the shelf sediment mixed layer and the impact of outcrop quality on trace fossil datasets.

Written by Jack Milligan and Romain Gougeon